The Price of (Artificial) Intelligence

The AI pricing models (and battles) that will rule the rest of your life.

In the wise words of Yoda — begun, the AI pricing wars have.

Anthropic drew the battle lines last week when they blogged about their plans to avoid ads in Claude at a time when OpenAI is slowly rolling out their ad-supported tiers. Anthropic then pre-released their own ads that ran during Sunday’s Super Bowl.

They’re funny ads, no doubt! But — their certainty about what’s right when it comes to ads and AI, and their own pricing, has flummoxed me.

I don’t like to be flummoxed for extended periods of time, so let’s talk it out!

Today, I want to posit that the price to access AI models and products will rule the rest of your life, and I hope to convince you to care.

Between Anthropic’s pre-release of ads and Sunday’s real-release, they launched an interesting update: fast mode for Opus 4.6. Anyone using Claude Code to do AI-generated coding work could type ‘/fast’ and they’d get the latest model at 2.5x the speed, and 6x the cost.

An individual, or a team, can now bypass a ‘wealthy-people’ paywall to access more intelligence (by way of more cognition per unit time).

When we use these AI models and products, speed, persistence, concurrency, and autonomy are key levers in the result. In other words, pricing is becoming a throttle on cognition. We could very easily wind up in a bifurcation of access to intelligence, fast lanes, and severe inequality.

AI and ads touch on your dinner plate.

Let’s zoom in on the current fight between Anthropic and OpenAI. First, let me give caveats: whether it’s OpenAI or others, ads and algorithms are going to be a part of this phase of technology, and a more important part than even the last phase.

We should hold companies to account about the implications, and I appreciate that OpenAI is consistently and repeatedly reaffirming that ads won’t influence AI results. There’s good reason to believe they’d adhere to this, too, but that’s for another day.

And while I respect Anthropic for staking out a principled position in public, it’s important to remember that a student in college with a few bucks to their name can access the same set of Google products as a wealthy oligarch today — because of the power of advertising.

While there are a bunch of incentive gradients that come out of ads around attention, distribution, and monopoly power, there’s no doubt that advertising subsidizes consumer demand that otherwise requires access to liquid capital — the news, apps, and large chunks of the web.

Both companies offer approximately the same business model to the world today: subscriptions ranging from $20 per month to $200 per month with incremental tiers of product and model access.

And let’s just get to the punchline: it’s not like Anthropic is going to give away versions of Claude that they’ll otherwise charge $20 for. And so if pricing models are gatekeepers to access, should they really be making fun of OpenAI for providing an ad-supported model that might get most of the population access to the latest GPT model when they’d be otherwise unable to afford it?

Ads are subsidies, and subsidies decide who gets in the building.

Pay-as-you-think pricing.

Let’s zoom in to another fast-moving area of intelligence bifurcation: the AI code generation tools that are being fast-adopted by the entire tech industry. For those less familiar, all now do approximately the same thing: users prompt, models write code.

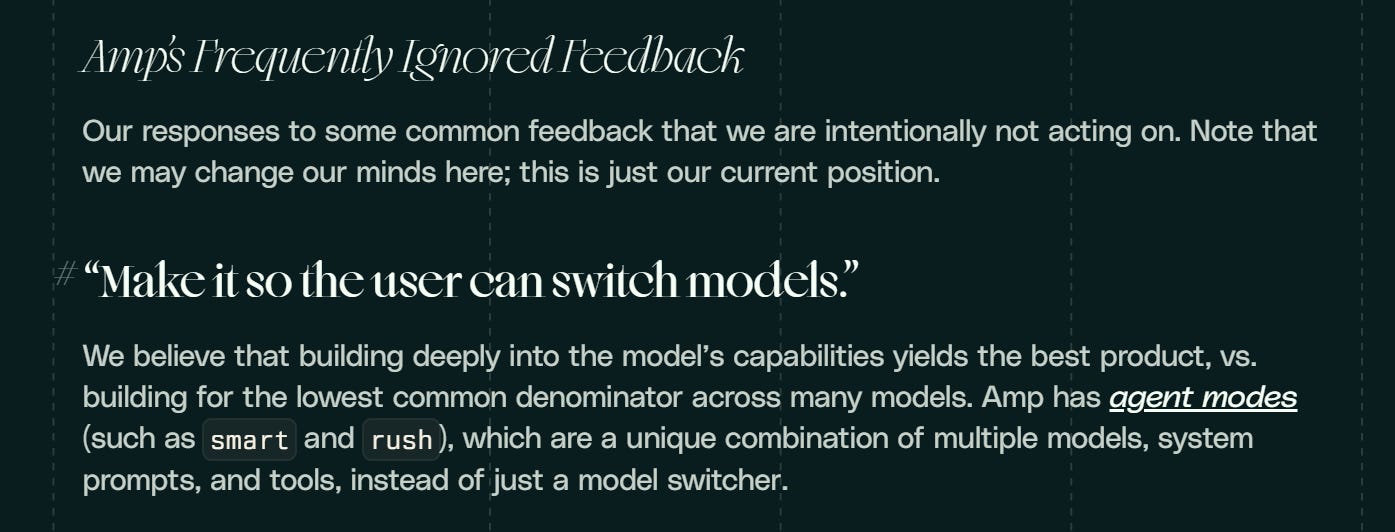

On one side, you have Amp Code, a startup that — from its launch — doesn’t have a subscription and whose CEO believes may never have one. They’re even principled against subscription pricing models. You can’t pay them $20 or $200 a month; you have to buy credits or pay as you go.

On the other side, you have subscription-oriented products like Cursor, Claude Code, or OpenAI’s Codex CLI. Although you can pay for extra tokens, these companies mostly want you to subscribe to their coding products for a monthly fee.

These two sides form what I call the token or the tether.

The token: Amp’s stated product and pricing philosophy: “Amp is unconstrained in token usage (and therefore cost). Our sole incentive is to make it valuable, not to match the cost of a subscription.” Translation: you’re paying for the credits, and so they’ll always try to serve you with the smartest model in the best harness, at its best settings, to achieve the result you want.

If that means you’re spending $5 one day on a task and $120 on another day to build an entire feature, they hope that’s an agreement you’re willing to engage in because you understand that the best, fastest way to get to a good result is the untethered token.

The tether: With subscription-oriented products like Cursor, companies are aiming for gym membership-style unit economics. They want a lot of people (and teams) to get engaged, subscribe to highest-tier bundles, and serve those users enough compute to keep them from churning while still winding up profitable.

But remember that, for the first time, the marginal cost of a digital product isn’t delivering deterministic bits of data. Instead, it’s the variable, probabilistic, and unpredictable cost of machine reasoning.

If an engineer wants to change how a login feature works, Opus 4 and Opus 4.5 might both be able to achieve it. There are capability gaps as you get to more complicated requests, but there’s also margin for getting crafty in using different models with different settings and harnesses to do a “good enough” job.

A subscription-oriented company wants to keep you making a reasonable number of requests, might swap to cheaper models as you use more of their service, or truncate the compute or reasoning that goes into your results to keep cost of goods sold (COGS) below average revenue per user (ARPU).

That’s the tether. They have good reasons to hold things back. This leads to new and interesting outcomes, like a dynamic I call the capability perception gap.

Point Amp Code at a bug and it’ll happily spawn dozens of tool calls until the test suite turns green. You’ll pay for that firehose of reasoning, but you know that it’ll try until it can’t anymore.

Whereas — Cursor has improved on this, but in parts of 2025, the company was clearly not letting the models “exercise” to their fullest power. You’d see users online feeling like the AI agent was “giving up” or “timing out” on complex tasks. The core model might’ve been the same as Amp’s, but it operated on a compute budget.

And users aren’t always told, and can’t always distinguish between genuine AI limitations and artificial business constraints. When an agent stops working on a problem, is it because the underlying model reached the edge of its capacity, or because the user hit some hidden throttle?

So — in one case, with subscription incentives, we might encounter throttling, model swaps, and good-enough behavior. Where we’re paying-as-we-go, we might get agents that think longer, better, faster, stronger.

How you’re being charged dictates the length of an agent’s leash.

Where’s my commission?

Let’s examine another dynamic, which is the transition away from software-as-a-service. It’s really about a transition away from buying product suites that you as the customer use to buying agents that do things — or, we used to buy features, and now we’ll move toward buying outcomes.

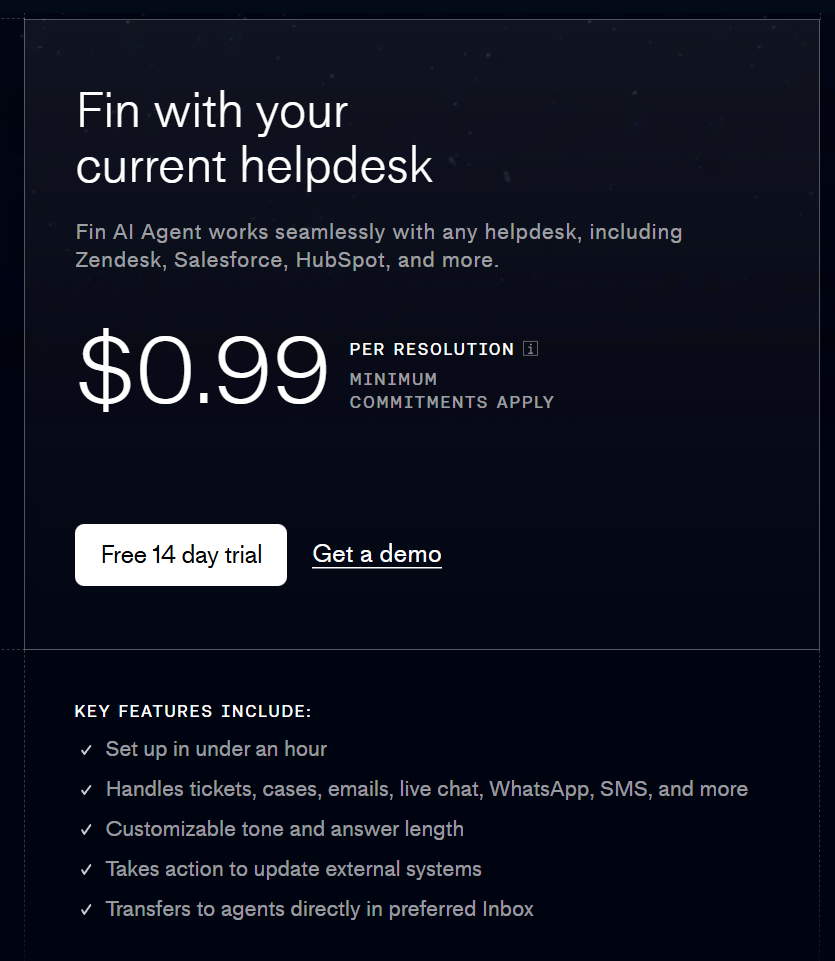

Think of it: in the past, if your company bought help desk software like Zendesk, you were paying for a set of features per user. Ultimately, the outcomes were still on the people at your company to achieve. And for Zendesk, the marginal cost of servicing an additional customer was essentially zero. Software-style economics.

In the age of intelligence, we’re flipping AI into equivalents of labor and agency. The customer service platform Intercom has been transitioning to Fin, its AI agent product that charges based on successful resolution of customer tickets.

Your company no longer cares how the job gets done (more or less), instead directly looking for the outcome they get at the end of an agentic chain. Although the company might wonder or want to get involved or steer the agent, this leaves a lot of the decision dynamics to Intercom (as a team) and Fin (as an autonomous agent).

And when pricing shifts from tools (limited by those who operate them) to outcomes (the companies that can deploy more models, faster models, smarter models win), customers will migrate to the better outcome regardless of cost. The capital advantage becomes the outcome advantage, rather than being a tool along the way.

Put differently — the nature of software as being paired with people is turning from linear to almost exponential, where although your company might still need 1 or 2 employees in customer service, they could be orchestrating 100+ agents working 24/7.

In this era, capital can buy almost-finished work.

Disney’s Fast Pass, but for life.

Did you notice? It all came together. This is about fast lanes, capital intelligence, and an uncapped top end.

Anthropic versus OpenAI demonstrates how access will be limited by business model, and will be unlocked by incremental capital.

Cursor versus Amp Code demonstrates that pricing will govern cognition, and how hard autonomous agents will try and persist.

Zendesk versus Finn demonstrates that we will increasingly purchase outcomes instead of tools, at uncapped or uncanny rates.

Put differently, access (who pays) → cognition throttle (how you pay) → outcomes for sale (what you buy) → capital buys not-before-seen compounding iteration speed.

Some of you might think this looks or sounds like the last era of software. It really isn’t. If you were a growth stage startup in 2019, you couldn’t just buy more Salesforce as a method of engaging and selling to more customers.

There was linearity — anchored to the human intelligence you had to hire — that is turning into some non-linear mode where you can buy more AI agents, in better and faster modes, leading to a multiplicative iteration effect.

If I start a banana stand, and you start a banana stand, and we both have five employees, there were always uneven dynamics between us. If I had capital access and raised venture, I had an advantage. But there were moderating forces at play, because I’d have to spend time converting that capital into people to exchange it for progress.

In 2026, I might use that venture capital to deploy hundreds of autonomous AI agents at 5x the speed of the generally available marketplace model in a way that you can’t even fathom to afford.

And look, I get what some of you will say. Competitive forces in the market will mean we get smarter models for cheaper over time. I agree with you! That’s already happening and it will continue to happen. But that’s about the baselines. In the age of autonomous AI agents, the top end of capability will likely remain uncapped.

Today, someone can buy Claude Code for $200/month and get the equivalent of one AI agent as a copilot for an entire work day. But a wealthier someone else can turn on fast mode, blast through the $200/month plan’s quotas, buy more tokens and get the equivalent of five AI agents as a copilot through that same work day, and then the rest of the week.

And this all matters until the point at which it might not — AGI or ASI, in which case I don’t have strong predictions. But until then, speed, autonomy, and concurrency of AI at the top end doesn’t seem to have hard caps.

Speed and concurrency are unlocks to non-linear advantage.

Democratization of intelligence.

I really respect both Anthropic and OpenAI, and I use both company’s products pretty much twenty hours a day. I appreciate Anthropic’s principled stands in most cases, but I think OpenAI is taking a more pragmatic approach as we see AGI and ASI on the horizon.

Funnily enough, this is adherence to their original mission to “advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole” (this has more recently been changed to “ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity,” for the record).

They seem not to think that the power of artificial intelligence should be held to the few, but instead distributed amongst the many. And implied in their strategy thus far: the path to that outcome might be the same that Google and Facebook and many others have walked — ads.

If there are other ways, we should find them, too.

Some of you might be asking — okay, so what next, bald man? To that, I’d say I got a hair system two months ago and I look 10 years younger and far less shiny.

But the other thing I’d say: I’m not sure. I can’t quite tell how much of this is tied to politics, although certainly some of it is. I’m more worried than I would be because of the existence of a tech oligarchy that seems likely to embrace extreme societal asymmetries.

At the same time, I want to continue to give breathing room to companies who seem to be exploring this in good faith — who are giving us smart models and products, or pre-thinking through the risks of rapid takeoff scenarios. And I want smart people to continue to get involved and join the conversation from a wider variety of industries and slices of life.

In the age of autonomous software, capital intelligence becomes a category we should pay attention to. The politics of access are more than cute memes about the ad you might get in your AI product. In fact, it could be about whether you’ll have access to AI products at all.